OS08: Virtual Memory I

Based on Chapter 6 of [Hai19]

(Usage hints for this presentation)

Computer Structures and Operating Systems 2022

Dr. Jens Lechtenbörger (License Information)

1. Introduction

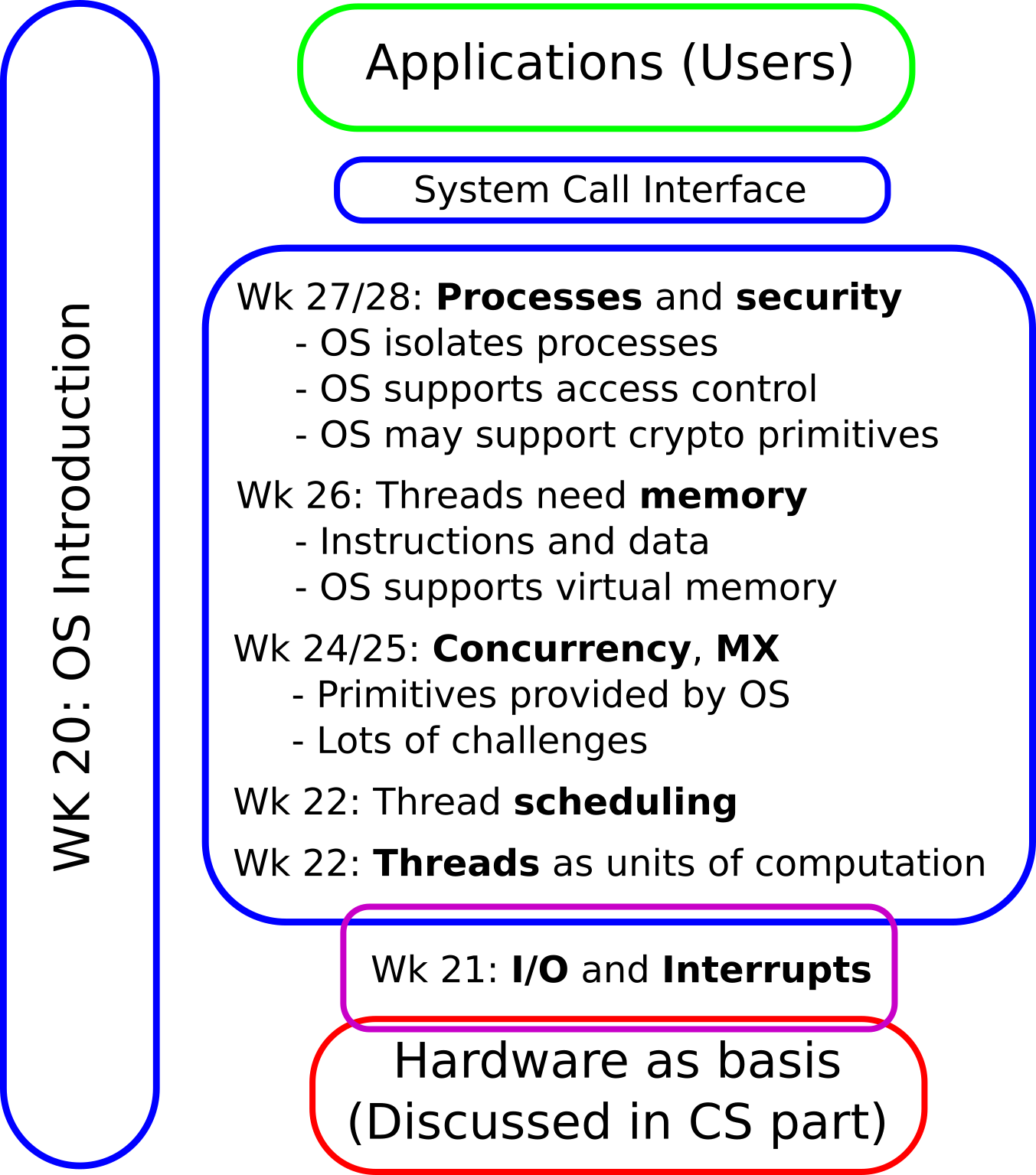

1.1. OS Plan

- OS Overview (Wk 20)

- OS Introduction (Wk 20)

- Interrupts and I/O (Wk 21)

- Threads (Wk 22)

- Thread Scheduling (Wk 22)

- Mutual Exclusion (MX) (Wk 24)

- MX in Java (Wk 25)

- MX Challenges (Wk 25)

- Virtual Memory I (Wk 26)

- Virtual Memory II (Wk 26)

- Processes (Wk 27)

- Security (Wk 28)

1.2. Today’s Core Questions

- What is virtual memory?

- How can RAM be (de-) allocated flexibly under multitasking?

- How does the OS keep track for each process what data resides where in RAM?

1.3. Learning Objectives

- Explain mechanisms and uses for virtual memory

- Including principle of locality and page fault handling

- Including access of data on disk

- Explain and perform address translation with page tables

1.4. Previously on OS …

1.4.1. Retrieval Practice

- How are processes and threads related?

- What happens when an interrupt is triggered (e.g., a page fault)?

1.4.2. Recall: RAM in Hack

1.5. Big Picture

1.6. Different Learning Styles

- The bullet point style may be particularly challenging for this presentation

- You may prefer this 5-page introduction

- It provides an alternative view on

- Topics of Introduction and Main Concepts

- Topics of section Paging

- After working through that text, you may want to jump directly

to the corresponding

JiTT tasks

to check your understanding

- Afterwards, come back here to look at the slides, in particular work through section Uses for Virtual Memory (not covered in the text)

- It provides an alternative view on

- Besides, Chapter 6 of [Hai19] is about virtual memory

Table of Contents

2. Main Concepts

2.1. Modern Computers

- RAM is byte-addressed (1 byte = 8 bits)

- Each

addressselects a byte (not a word as in Hack)- (Machine instructions typically operate on words (= multiple bytes), though)

- Each

- Physical vs virtual addresses

- Physical: Addresses used on memory bus

- Hack

address

- Hack

- Virtual: Addresses used by threads and CPU

- Do not exist in Hack

- Physical: Addresses used on memory bus

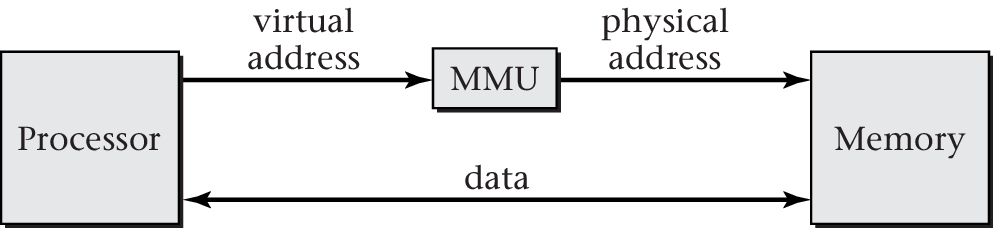

2.2. Virtual Addresses

- Additional layer of abstraction provided by OS

- Programmers do not need to worry about physical memory locations at all

- Pieces of data (and instructions) are identified by virtual addresses

- At different points in time, the same piece of data (identified by its virtual address) may reside at different locations in RAM (identified by different physical addresses) or may not be present in RAM at all

- OS keeps track of (virtual) address spaces:

What (virtual address) is located where (physical address)

- Supported by hardware, memory management unit (MMU)

- Translation of virtual into physical addresses (see next slide)

- Supported by hardware, memory management unit (MMU)

2.2.1. Memory Management Unit

“Figure 6.4 of [Hai17]” by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0; converted from GitHub

2.3. Processes

- OS manages running programs via processes

- More details in upcoming presentation

- For now: Process ≈ group of threads that share a virtual

address space

- Each process has its own address space

- Starting at virtual address 0, mapped

per process to RAM by the OS, e.g.:

- Virtual address 0 of process P1 located at physical address 0

- Virtual address 0 of process P2 located at physical address 16384

- Virtual address 0 of process P3 not located in RAM at all

- Processes may share data (with OS permission), e.g.:

BoundedBufferlocated at RAM address 42- Identified by virtual address 42 in P1, by 4138 in P3

- Starting at virtual address 0, mapped

per process to RAM by the OS, e.g.:

- Address space of process is shared by its threads

- E.g., for all threads of P2, virtual address 0 is associated with physical address 16384

- Each process has its own address space

2.4. Pages and Page Tables

- Mapping between virtual and physical addresses does not happen at

level of bytes

- Instead, larger blocks of memory, say 4 KiB

- Blocks of virtual memory are called pages

- Blocks of physical memory (RAM) are called (page) frames

- Instead, larger blocks of memory, say 4 KiB

- OS manages a page table per process

- One entry per page

- In what frame is page located (if present in RAM)

- Additional information: Is page read-only, executable, or modified (from an on-disk version)?

- One entry per page

2.4.1. Page Fault Handler

- Pages may or may not be present in RAM

- Access of virtual address whose page is in RAM is called

page hit

- (Access = CPU executes machine instruction referring to that address)

- Otherwise, page miss

- Access of virtual address whose page is in RAM is called

page hit

- Upon page miss, a page fault is triggered

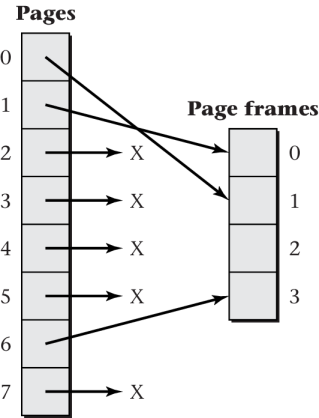

2.5. Drawing for Page Tables

The page table

Figure © 2016 Julia Evans, all rights reserved; from julia's drawings. Displayed here with personal permission.

3. Uses for Virtual Memory

3.1. Private Storage

- Each process has its own address space, isolated from others

- Autonomous use of virtual addresses

- Recall: Virtual address 0 used differently in every process

- Underlying data protected from accidental and malicious

modifications by other processes

- OS allocates frames exclusively to processes (leading to disjoint portions of RAM for different processes)

- Unless frames are explicitly shared between processes

- Next slide

- Autonomous use of virtual addresses

- Processes may partition address space

- Read-only region holding machine instructions, called text

- Writable region(s) holding rest (data, stack, heap)

3.2. Controlled Sharing

- OS may map limited portion of RAM into multiple address spaces

- Multiple page tables contain entries for the same frames then

- See

smemdemo later on

- See

- Multiple page tables contain entries for the same frames then

- Shared code

- If same program runs multiple times, processes can share text

- If multiple programs use same libraries (libXYZ.so under GNU/Linux, DLLs under Windows), processes can share them

3.2.1. Copy-On-Write Drawing

Copy on write

Figure © 2016 Julia Evans, all rights reserved; from julia's drawings. Displayed here with personal permission.

3.2.2. Copy-On-Write (COW)

- Technique to create a copy of data for second process

- Data may or may not be modified subsequently

- Pages not copied initially, but marked as read-only with

access by second process

- Entries in page tables of both processes point to original frames

- Fast, no data is copied

- If process tries to write read-only data, MMU triggers interrupt

- Handler of OS copies corresponding frames, which then

become writable

- Copy only takes place on write

- Afterwards, write operation on (now) writable data

- Handler of OS copies corresponding frames, which then

become writable

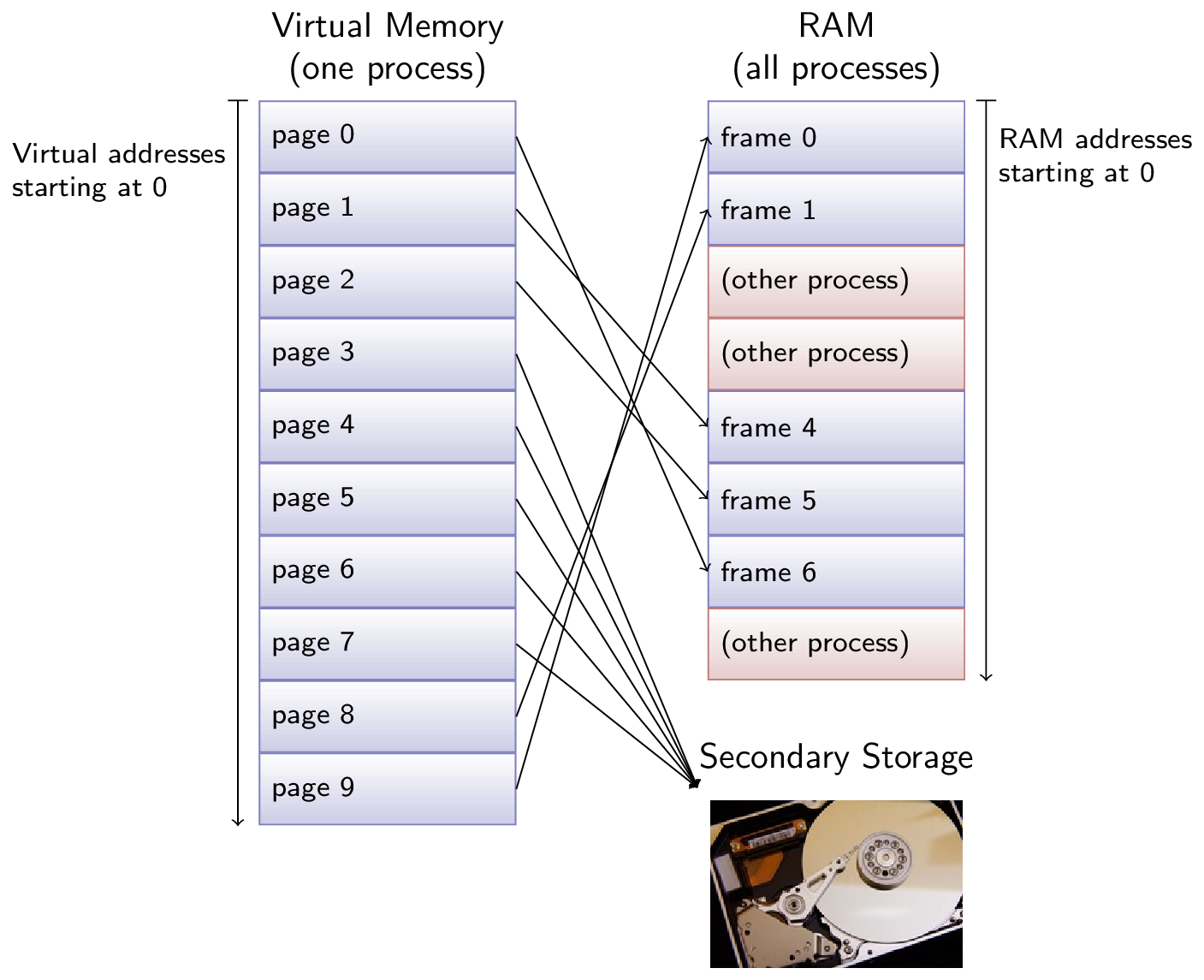

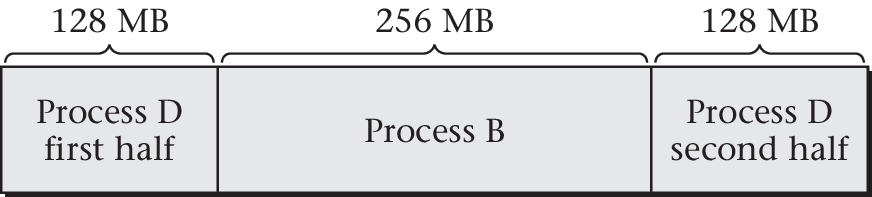

3.3. Flexible Memory Allocation

- Allocation of RAM does not need to be contiguous

- Large portions of RAM can be allocated via individual frames

- Which may or may not be contiguous

- See next slide or big picture

- The virtual address space can be contiguous, though

- Large portions of RAM can be allocated via individual frames

3.3.1. Non-Contiguous Allocation

“Figure 6.9 of [Hai17]” by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0; converted from GitHub

3.4. Persistence

- Data kept persistently in files on secondary storage

When process opens file, file can be mapped into virtual address space

- Initially without loading data into RAM

- See

page 3in big picture

- See

- Page accesses in that file trigger page faults

- Handled by OS by loading those pages into RAM

- Marked read-only and clean

- Handled by OS by loading those pages into RAM

- Upon write, MMU triggers interrupt, OS makes page writable and

remembers it as dirty (changed from clean)

- Typically with MMU hardware support via dirty bit in page table

- Dirty = to be written to secondary storage at some point in time

- After being written, marked as clean and read-only

- Initially without loading data into RAM

3.5. Demand-Driven Program Loading

- Start of program is special case of previous slide

- Map executable file into virtual memory

- Jump to first instruction

- Page faults automatically trigger loading of necessary pages

- No need to load entire program upon start

- Faster than loading everything at once

- Reduced memory requirements

3.5.1. Working Set

- OS loads part of program into main memory

- Resident set: Pages currently in main memory

- At least current instruction (and required data) necessary in main memory

- Principle of locality

- Memory references typically close to each other

- Few pages sufficient for some interval

- Working set: Necessary pages for some interval

- Aim: Keep working set in resident set

- Replacement policies in next presentation

- Aim: Keep working set in resident set

4. Paging

4.1. Major Ideas

- Virtual address spaces split into pages, RAM into frames

- Page is unit of transfer by OS

- Between RAM and secondary storage (e.g., disks)

- Each virtual

addresscan be interpreted in two ways- Integer number (

addressas binary number, as in Hack) - Hierarchical object consisting of page number and offset

- Page number, determined by most significant bits of

address - Offset, remaining bits of

address= byte number within its page- (Detailed example follows)

- Page number, determined by most significant bits of

- Integer number (

- Page is unit of transfer by OS

- Page tables keep track of RAM locations for pages

- If CPU uses virtual address whose page is not present in RAM, the Page fault handler takes over

4.2. Sample Memory Allocation

Sample allocation of frames to some process

![Figure 6.10 of cite:Hai17]()

“Figure 6.10 of [Hai17]” by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0; converted from GitHub

4.3. Page Tables

- Page Table = Data structure managed by OS

- Per process

- Table contains one entry per page of virtual address space

- Each entry contains

- Frame number for page in RAM (if present in RAM)

- Control bits (not standardized, e.g., valid, read-only, dirty, executable)

- Note: Page tables do not contain page numbers as they are implicitly given by row numbers (starting from 0)

- Note on following sample page table

- “0” as valid bit indicates that page is not present in RAM, so value under “Frame#” does not matter and is shown as “X”

- Each entry contains

4.3.1. Sample Page Table

Consider previously shown RAM allocation (Fig. 6.10)

![Figure 6.10 of cite:Hai17]()

“Figure 6.10 of [Hai17]” by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0; converted from GitHub

Page table for that situation (Fig. 6.11)

Valid Frame# 1 1 1 0 0 X 0 X 0 X 0 X 1 3 0 X

4.3.2. Address Translation Example (1/3)

- Task: Translate virtual address to physical address

- Subtask: Translate bits for page number to bits for frame number

- Suppose

- Pages and frames have a size of 1 KiB (= 1024 B)

- 15-bit addresses, as in Hack

- Consequently

- Size of address space: 215 B = 32 KiB

- 10 bits are used for offsets (as 210 B = 1024 B)

- The remaining 5 bits enumerate 25 = 32 pages

4.3.3. Address Translation Example (2/3)

- Hierarchical interpretation of 15-bit addresses

- Virtual address: 5 bits for page number 10 bits for offset

- Physical address: 5 bits for frame number 10 bits for offset

- Based on page table

- Page 0 is located in frame 1

- Page 0 contains virtual addresses

between 0 and 1023, frame 1 physical

addresses between 1024 and 2047

- Consider virtual address 42

- 42 = 00000 0000101010

- Page number = 00000 = 0

- Offset = 0000101010 = 42

- 42 is located at physical address 00001 0000101010 = 1066 (= 1024 + 42)

- 42 = 00000 0000101010

- Consider virtual address 42

4.3.4. Address Translation Example (3/3)

- Based on page table

- Page 6 is located in frame 3

- Page 6 contains addresses

between 6*1024 = 6144 and 6*1024+1023 = 7167

- Consider virtual address 7042

- 7042 = 00110 1110000010

- Page number = 00110 = 6

- Offset = 1110000010 = 898

- In general, address translation exchanges

page number with

frame number

- Here, 6 with 3

- 7042 is located at physical address 00011 1110000010 = 3970 (= 3*1024 + 898)

- 7042 = 00110 1110000010

- Consider virtual address 7042

4.4. JiTT Tasks

4.4.1. JiTT: Address Translation

Answer the following questions in Learnweb.

Suppose that 32-bit virtual addresses with 4 KiB pages are used.

- How many bits are necessary to number all bytes within pages?

- How many pages does the address space contain? How many bits are necessary to enumerate them?

- Where within a 32-bit virtual address can you “see” the page number?

4.4.2. JiTT: A quiz

4.5. Challenge: Page Table Sizes

- E.g., 32-bit addresses with page size of 4 KiB (212 B)

- Virtual address space consists of up to 232 B = 4 GiB = 220 pages

- Every page with entry in page table

- If 4 bytes per entry, then 4 MiB (222 B) per page table

- Page table itself needs 210 pages/frames! Per process!

- Much worse for 64-bit addresses

- Virtual address space consists of up to 232 B = 4 GiB = 220 pages

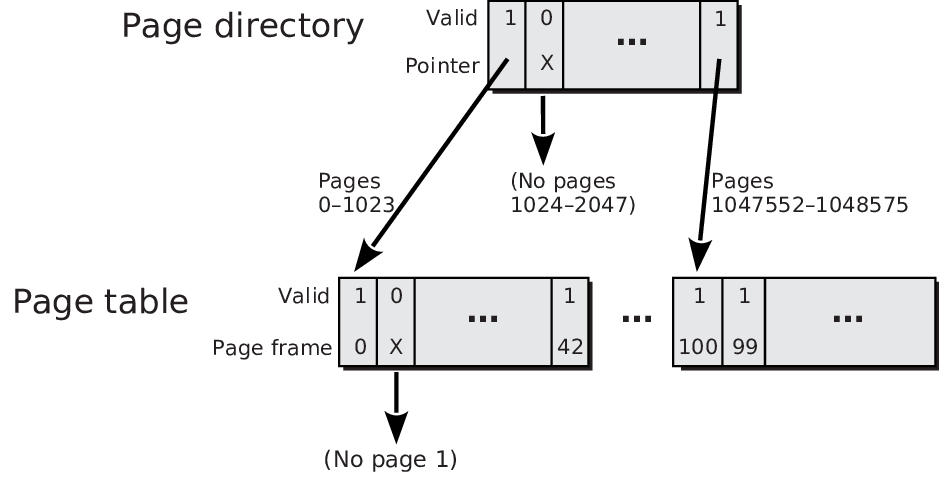

- Solutions to reduce amount of RAM for page tables

- Multilevel (or hierarchical)

page tables (2 or more levels)

- Tree-like structure, efficiently representing large unused areas

- Root, called page directory

- 4 KiB with 210 entries for page tables

- Each entry represents 4 MiB of address space

- Inverted page tables in next presentation

- Multilevel (or hierarchical)

page tables (2 or more levels)

5. Multilevel Page Tables

5.1. Core Idea

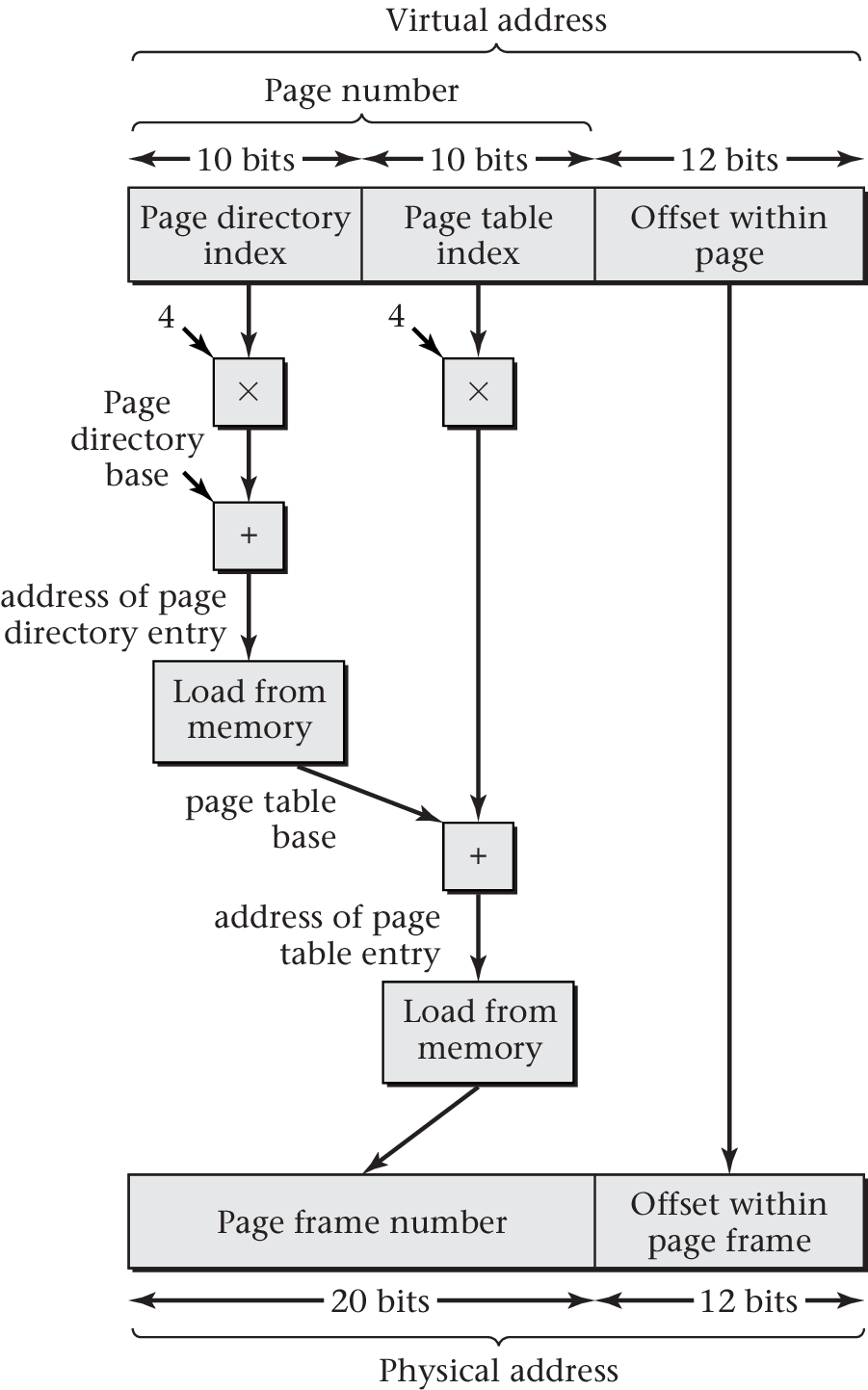

- So far: Virtual address is hierarchical object consisting of page number and offset

- Now multilevel page tables: Interpret page table as tree with

fixed depth, i.e., a fixed number of multiple levels

- (Visualizations on next two slides)

- For depth n, split page number into n smaller parts

- Two-level: Split 20 bits into two parts with 10 bits each

- To traverse page table (tree), use one part on each level

- Aside: On 64-bit machines, Linux uses 5-level tables by default since 2019-09-16

5.2. Two-Level Page Table

“IA-32 two-level page table” by Jens Lechtenbörger under CC BY-SA 4.0; Frame numbers and valid bits added to and third layer removed from Figure 6.13 of [Hai17] by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0. Source at GitLab.

Note: Page table contains entries of an ordinary page table. Previously, valid bit and page frame numbers were shown in columns; here, they are shown in rows.

5.2.1. Two-Level Address Translation

“Figure 6.14 of [Hai17]” by Max Hailperin under CC BY-SA 3.0; converted from GitHub

5.3. JiTT: Questions, Feedback, Survey

- This slide serves as reminder that I am happy to obtain and provide feedback for course topics and organization. If contents of presentations are confusing, you could describe your current understanding (which might allow us to identify misunderstandings), ask questions that allow us to help you, or suggest improvements (maybe on GitLab). Please use the session’s shared document or MoodleOverflow. Most questions turn out to be of general interest; please do not hesitate to ask and answer where others can benefit. If you created additional original content that might help others (e.g., a new exercise, an experiment, explanations concerning relationships with different courses, …), please share.

- Please take some minutes to answer this anonymous survey in Learnweb on your thoughts related to Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT) and the presentation format for Operating Systems.

6. Looking at Memory

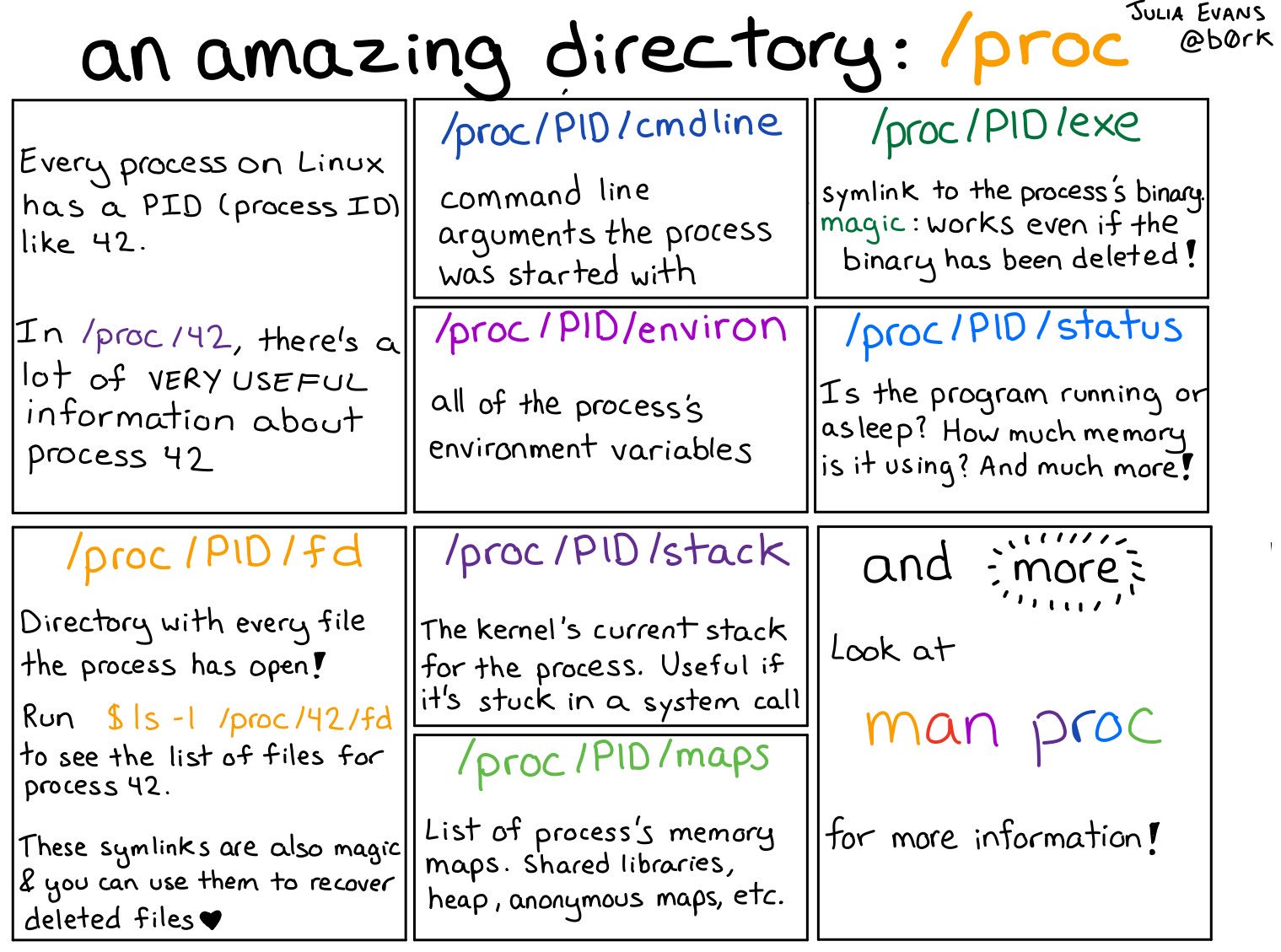

6.1. Linux Kernel: /proc/<pid>/

/procis a pseudo-filesystem- See https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man5/proc.5.html

- (Specific to Linux kernel; incomplete or missing elsewhere)

- “Pseudo”: Look and feel of any other filesystem

- Sub-directories and files

- However, files are no “real” files but meta-data

- Interface to internal kernel data structures

- One sub-directory per process ID

- OS identifies process by integer number

- Here and elsewhere,

<pid>is meant as placeholder for such a number

- See https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man5/proc.5.html

6.1.1. Video about /proc

6.1.2. Drawing about /proc

/proc

Figure © 2018 Julia Evans, all rights reserved; from julia's drawings. Displayed here with personal permission.

6.1.3. Drawing about man pages

Man pages are amazing

Figure © 2016 Julia Evans, all rights reserved; from julia's drawings. Displayed here with personal permission.

6.2. Linux Kernel Memory Interface

- Memory allocation (and much more) visible under

/proc/<pid> - E.g.:

/proc/<pid>/pagemap: One 64-bit value per virtual page- Mapping to RAM or swap area

/proc/<pid>/maps: Mapped memory regions/proc/<pid>/smaps: Memory usage for mapped regions

- Notice: Memory regions include shared libraries that are used by lots of processes

6.3. GNU/Linux Reporting: smem

- User space tool to read

smapsfiles:smem - Terminology

- Virtual set size (VSS): Size of virtual address space

- Resident set size (RSS): Allocated main memory

- Standard notion, yet overestimates memory usage as lots of

memory is shared between processes

- Shared memory is added to the RSS of every sharing process

- Standard notion, yet overestimates memory usage as lots of

memory is shared between processes

- Unique set size (USS): memory allocated exclusively to process

- That much would be returned upon process’ termination

- Proportional set size (PSS): USS plus “fair share” of shared pages

- If page shared by 5 processes, each gets a fifth of a page added to its PSS

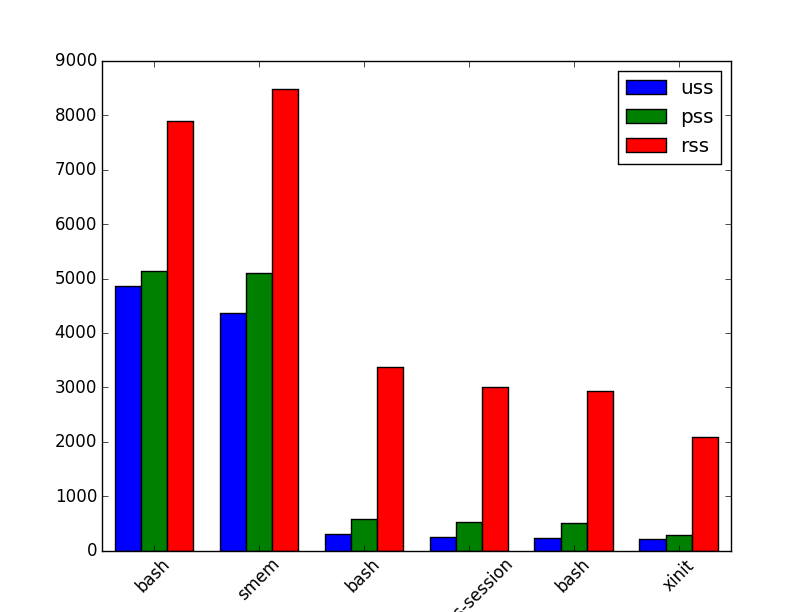

6.3.1. Sample smem Output

$ smem -c "pid command uss pss rss vss" -P "bash|xinit|emacs" PID Command USS PSS RSS VSS 765 /usr/bin/xinit /etc/X11/Xse 220 285 2084 15952 1390 /bin/bash -c libreoffice5.3 240 510 2936 13188 826 /bin/bash /usr/bin/qubes-se 256 524 3008 13204 750 -su -c /usr/bin/xinit /etc/ 316 587 3368 21636 1251 bash 4864 5136 7900 26024 2288 /usr/bin/python /usr/bin/sm 5272 6035 9432 24688 1145 emacs 90876 93224 106568 662768

6.3.2. Sample smem Graph

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary

- Virtual memory provides abstraction over RAM and secondary storage

- Paging as fundamental mechanism

- Isolation of processes

- Stable virtual addresses, translated at runtime

- Paging as fundamental mechanism

- Page tables managed by OS

- Address translation at runtime

- Hardware support via MMU with TLB

- Multilevel page tables represent unallocated regions in compact form

Bibliography

- [Hai19] Hailperin, Operating Systems and Middleware – Supporting Controlled Interaction, revised edition 1.3.1, 2019. https://gustavus.edu/mcs/max/os-book/

License Information

This document is part of an Open Educational Resource (OER) course on Operating Systems. Source code and source files are available on GitLab under free licenses.

Except where otherwise noted, the work “OS08: Virtual Memory I”, © 2017-2022 Jens Lechtenbörger, is published under the Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0.

In particular, trademark rights are not licensed under this license. Thus, rights concerning third party logos (e.g., on the title slide) and other (trade-) marks (e.g., “Creative Commons” itself) remain with their respective holders.